Politics

How the BJP weaponised evictions as a tool against Assam’s Bengali Muslim residents

Quote Posted on Updated on

On 8 March, the KAAC officials, police officers and paramilitary personnel returned to the Hojai-Karbi Anglong eviction site for a third round of evictions. But the eviction was halted by the intervention of the Gauhati high court, which issued an order that day, taking note of Borgohain’s letters and instructing the chief secretary to “stop the eviction drive before final boundary demarcation is done.”

The high court’s order did not prevent police excesses at the eviction site, where a group of residents were protesting against the drive. In the afternoon, while I was visiting Kulsuma Begum at the hospital, Ain Uddin, a 29-year-old resident of the area, called me to inform me that the police was lathi charging the protestors. In the background, I could hear people screaming and praying. A short while later, he sent me several photographs of the police assault—one image showed a traumatised-looking old man with a white beard, standing with the support of two young men. Uddin had added the caption, “Police has broken his leg.”

The BJP had begun the practice of evictions soon after forming the government. On 6 February 2017, Pallab Lochan Das, the state’s revenue minister, informed the assembly that the government had evicted 3,481 families from 17 districts across Assam within the first six months of coming to power. Since then, the state government has continued to conduct large-scale eviction operations across the state, but it has not provided any data concerning the drives. Bhabesh Kalita, the minister of state in the revenue and disaster management department, told me he did not have updated data because the evictions drives were still ongoing. Though precise demographic statistics are unavailable, most of the evictions have taken place in Muslim-dominated areas, and have also led to the displacement of Adivasi communities in some cases.

My colleagues and I have been visiting the eviction sites to document as much as is possible. Over the last three years, I have visited at least ten eviction sites across Assam. A clear pattern emerges from studying these evictions—the Muslims residents of an area are described as Bangladeshi illegal immigrants, an eviction drive is carried out without prior notice or compliance with such procedural requirements, and it is marked by the use of brute force and impunity for those responsible. This modus operandi was visible in the BJP-led state government’s first eviction operation, in September 2016, near Kaziranga National Park, in central Assam’s Nagaon district.

On 19 September, following an October 2015 Gauhati high court order, the state government conducted an eviction drive in three villages—Bandardubi, Deosursang and Palkhuwa—located on the periphery of the Kaziranga National Park. During the drive, the government destroyed the houses of nearly two hundred families—all but seven of these belonged to Muslims. The police shot two people dead, including a 12-year-old girl; several were injured in police firing and lathi charges. Soon after the eviction drive was conducted, Himanta Biswa Sarma, the state finance minister, posted a tweet congratulating the district administration and declaring that the BJP government would “never compromise on JATI, MATI & BHETI.”

CURRENT ISSUE

Around two weeks later, I went to the eviction site as part of a fact-finding team of academicians and activists. At the office of a farmers’ collective near Kaziranga, one of the farmers showed me his land documents and said, “We are neither encroachers nor illegal Bangladeshi immigrants, we were evicted from our patta land”—referring to the official land-holding document. Even government records reveal that Bandardubi and Deosursang villages were given the patta in 1961, whereas Kaziranga was declared a national park only in 1974. In fact, Abdul Hamid, one of the victims of the eviction violence, gave me certified copies of land records that clearly stated that the land does not fall within the national park’s demarcated area. He also gave me a copy of a six-month old revenue receipt and said, “I have been paying the revenue regularly, how could the government evict me without resettlement?”

None of the mainstream Assamese media houses reported on the apparent illegality of the eviction. Instead, the media largely portrayed the victims as illegal Bangladeshi immigrants who encroached upon the land of the indigenous Assamese. After the Hojai-Karbi Anglong eviction too, the media continued the same narrative. I spoke to a journalist who covered the eviction for one of the oldest and most widely circulated English dailies in Assam, whose story framed the victims as “illegal Bangladeshi immigrants.” When I asked him how he was certain that they were Bangladeshi nationals, he argued that he has to call them “Bangladeshi” because the politicians and the people in position of power have identified them as such. The journalist requested not to be identified out of fear for his safety.

The next morning, I experienced the reach and might of the Assam government first-hand, during my attempt to carry out a fact-finding mission at the eviction site. Upon reaching Lanka railway station in Hojai district, I got a call from a police officer summoning me to the Lanka police station. I informed the police officer that I was waiting for a colleague and that we would come to the station together. But over the next ten minutes, the police called me not less than ten times. At the police station, at least five officers, including a deputy and additional superintendent of police as well as an officer of the special branch, questioned us for almost seven hours.

The officers were polite and served us snacks, but they were relentless. They asked me why I was interested in knowing about the situation, about my background, about where I work and for whom I write, and about the international news organisations for which I have written or given an interview. The police officers were particularly suspicious about my connection with Al Jazeera, the news website for which I was reporting on the evictions at the time, treating it not as an international media platform, but almost as an outlawed organisation.

Eventually, the police refused to let us visit the eviction site or meet the deputy commissioner Borgohain. The deputy commissioner later told me over phone that the police had prevented us from visiting the site “in fear that our visit would escalate tensions in the area.” He evaded questions about why the state administration had proceeded with the eviction drive despite his letters. I tried contacting Alok Kumar, the chief secretary of Assam, and Mahananda Hazarika, the principal secretary of the KAAC, to ask why they did not take heed of the deputy commissioners concerns about the eviction. Hazarika asked me to visit the KAAC office, but did not respond to messages or calls seeking a phone interview. Kumar did not respond to multiple calls and messages.

Over the last few months, the BJP’s popularity in Assam has been on a downward spiral. The disaffection with the party began with the BJP’s introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Bill, in 2016, which sought to give citizenship to all the immigrants except Muslims, whereas even the BJP’s Assamese allies are opposed to the Hindu immigrants from Bangladesh. While the BJP appears to have brokered peace with its allies ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, in Assam’s tribal areas such as the Karbi Anglong, the disillusionment is compounded by allegations of rampant corruption in handling the funds allocated to the autonomous council and the KAAC’s proposal to allot land in the area for a Patanjali herbal and food park to the business tycoon Ramdev. The Hojai-based activist Rahman, who is the president of the Hojai unit of the Krishak Mukti Sangram Samiti—a peasants-rights organisation in Assam—said that the BJP was losing ground in the Diphu Lok Sabha constituency, which consists of the autonomous districts Dima Hasao and Karbi Anglong.

“The BJP was in desperate need of a situation through which they could consolidate the tribal vote before the general election,” Rahman said. “What could be more appropriate than orchestrating an eviction drive against the Muslims, that too, through which the BJP can claim that they got back the council’s land, which was never under their possession.” Prafulla Nath, an assistant professor with the centre for tribal studies at Assam University’s Diphu campus, said that the BJP government could exploit the situation by portraying the situation as an encroachment of tribal land by the Muslims residents. “The government knew that if the eviction is done by the Hojai district, there would be lots of hue and cry,” Nath said. “As it is done by Karbi Anglong administration, they can use the tribal card.”

In the wake of the Citizenship Amendment Bill protests, ministers in the Assam government resorted to spreading communal and polarising rhetoric, terming the state’s Muslims as illegal immigrants who snatched land and resources from the indigenous Assamese people. For instance, in 2016, the finance minister Sarma began spreading misinformation that Muslim residents had encroached upon the land belonging to a satra—socio-religious monasteries established by Srimanta Sankardev, the architect of modern Assamese society.

For the Assamese, the satras are an emotive part of their state and culture, and Sarma sought to invoke their pride in order to exploit it and target the Muslims. “Does secularism mean that the satras have to move out of their original places?” Sarma asked in a November 2016 press conference. “Does secularism mean some people will snatch away land belonging to Batadrava satra? Does secularism mean some people will encroach upon land in Kaziranga and Pobitora?” But Sarma’s inflammatory rhetoric was defeated when Kalita placed government records before the state assembly, which revealed that the satra land was not encroached by the so-called Bangladeshi Muslims, but that it was eroded by the Brahmaputra river, and that the government had failed to protect it.

In present-day Assam, no one questions the government—not even the human-rights organisations. Once in January 2017, when I was talking to a senior officer of an international child-rights organisation, my friend sent me a photograph of the dead body of a three-day-old infant, who had died in a resettlement camp a few days after an eviction drive in Sipajhar town, in Assam’s Darrang district. I showed him the photograph and requested to do something for the evicted children. “Officially I cannot do anything, Abdul,” he replied. “This is a different government. But if you ask me personally, I would be happy to donate something.”

During the Kaziranga fact-finding mission, one experience was particularly telling of the fearful conditions prevailing at the resettlement camps. At one of the camps, I saw a young boy curiously looking at us. When I opened the lens of my camera to take a picture of him, the boy cried out loud and his mother rushed out from her shelter and immediately took him into her lap. The mother explained that since the eviction, her son lives in fears of the “khaki dress and anything that resembles a gun.” The incident brought to mind a disturbing parallel—the viral photo of a Syrian girl who surrendered to a camera, mistaking it to be a gun.

Originally published at https://caravanmagazine.in/religion/bjp-weaponised-evictions-tool-assam-muslim-residents

Growing up Miya in Assam: How the NRC weaponised my identity against me

Quote Posted on Updated on

He has settled down now. He has many friends. Every day, he has a new story to tell. In the living room of our rented house he often plays with our landlord’s young daughter. They sometimes sing together: “bilote halise dhunia podumi phool”—In the pond a lotus sways. I never had the flawless Assamese pronunciation that he has already acquired in the first three years of his life. Listening to him, I feel immensely proud.

But when I look at him, I also feel immense fear.

I am reminded of my own childhood. My father never told me that the world outside his warmth and protection would be hostile to me. This only became apparent to me when I first visited Guwahati. It was here that I first realised that I have another identity, a subordinate identity—I was a miya, a Bengali-origin Muslim, seen in Assam as an outsider, a suspected Bangladeshi.

Every year, a large number of people from my native place in Barpeta district of western Assam migrate seasonally to Guwahati to work in various unorganised sectors. When I was 14 years old, I went to see the city and write a homework essay on how I spent my summer break. Late one afternoon, my uncle Sirajul Haque and I were waiting to cross a busy road in Guwahati’s Lalganesh area. My uncle, who was then in his forties, had not been keeping well for two days, and had been unable to ply his rickshaw.

A group of young men stood nearby. They asked him to help push start a vehicle. My uncle began telling them about his health. The words had barely left his mouth when the young men began cursing at him. They called him “Kela Miya” and “Bangladeshi” while kicking him. My middle-aged uncle pleaded for mercy with folded hands, but the young men did not relent. I was scared and fled the scene. I ran down a dark lane and disappeared, reaching the rented tenement where we were staying. Uncle also returned after a while. He didn’t go to the pharmacy. As my other relatives prepared the evening meal, he lay in one corner and would not speak to anyone. He could not eat properly. I also kept quiet, did not tell anyone about the incident. I could not sleep that night. Whenever I closed my eyes, the image of my uncle played again and again, like a motion picture.

I came back to my village with a heavy heart. I could not write that essay. For some reason, I resolved that day that I would continue to study, at any cost. I wanted to be Assamese—a better Axomiya then anyone else, whose identity cannot be questioned by anyone. I learned the language. I imbibed the cuisine. I immersed myself in the tunes of Bihu songs. I did not realise when this became my life’s biggest mission—from my classroom to my workplace, from my emotions to my imagination, my focus was to be Axomiya.

But every so often, I would be reminded that my efforts to be Axomiya were not enough. My accent was not pure—I was reminded that the dialect I spoke at home was filthy. I was warned that my lungi could not be a part of Axomiya identity. I was reminded that my ancestors were not the sons and daughters of this soil.

Sometimes these warnings were violent—either verbal or physical—but sometimes, they were devoid of any action. I studied law for a few years at Assam University in Silchar, although I was unable to complete the course due to financial constraints. Silchar, a town in the Barak Valley, is known as the heartland for Bengali nationalism in Assam. One day, I met an Assamese senior in the hostel. We introduced ourselves. When I told him where I lived—an address in the Barpeta district—he nonchalantly replied, “Oh, tumi Miya?”—You’re a Miya? When I said yes, he silently walked away down the stairs, as if uninterested in talking to a Miya. I could not move for a few moments. I never had the courage to talk to him again.

I often wonder what makes him—and others like him—so powerful, and me so vulnerable. I ask myself why I felt subordinate in the first place. Why did I not revolt against the young men who punched my uncle? Why didn’t I kick them back? What made me think the quality of their Assamese accent, the language and culture they possess is superior? What compelled me to think that without imitating their way of life, I could not be a dignified Assamese? Why can’t my accent, my dialect, my costume and culture be the part of the greater Assamese identity?

The answer lies in the century-long histories of oppression, persecution and production of unlimited fear. Miya Muslims like me are not part of the Assamese vision, which begins and ends with the indigenous Axomiyas. Though we have been living and working on this land for centuries—often for the so-called indigenous Axomiyas—we are not to be allowed in. This xenophobia has been formalised in the National Register of Citizens, which threatens to delegitimise any person who cannot prove their credentials to the satisfaction of the Axomiya state. It has weaponised all aspects of our identity, using them to keep us out of our own state and nation.

*

My uncle, who was abused by the so-called sons of the soil, has lost his soil to the erosion of the river Beki, one of the ferocious tributaries of the mighty Brahmaputra. Every year in Assam, thousands of people living on the chars—riverine islands—and along river banks, mostly Miya Muslims, get uprooted because of erosion. The Brahmaputra and its tributaries swell during the rains, swallowing parts of the chars and leaving their residents with no choice but to move inland. In any other part of the country, the victims of such erosion would be likely to receive compensation and rehabilitation from the government, or at least ask for it. In 1995, my uncle lost his land to the river and shifted to our village, hardly three kilometres from his previous home. Instead of a rehabilitation grant, he was served a notice by the Foreigners Tribunal, asking him to prove his Indian nationality.

He was not the only person in the family whose identity fell under suspicion after they moved inland. His elder brother, who also settled in our village along with him, was marked a D-voter—a “doubtful” voter, suspected of being an illegal Bangladeshi immigrant and required to prove his identity before the tribunal as well. Though our village is hardly seven kilometres from the district headquarters, it still does not have access to all-weather roads. Throughout the summer and monsoon months, our houses remain surrounded by water. Often, my uncle would call out my name in his loud voice, telling me to come to his house, or he would sail his banana raft across the water to come to ours. We would discuss the progress of their cases. In these conversations, he would appear confident in his ability to prove his Indian nationality. But I could see the fear and anxiety on his face.

This is the cost my uncle paid to defend his Indian citizenship—the life of his elder brother, then five bighas of land, which he sold to cover the court expenses. After his brother’s death, my uncle also became responsible for four more family members. He risked the abuse of being called a Bangladeshi once again, and went back to Guwahati to pull a rickshaw so that he could feed his family.

My uncles are not my only relatives to be labelled D-voters. In 1997, nearly four lakh people across the state—mostly Miya Muslims and Bengali Hindus—were marked D-voters. Two members of my extended family made this list—a widowed aunt, and another uncle. My aunt became a widow at a very early age. She had a tough time looking after her five minor children. Being designated a D-voter increased her vulnerability, but her indomitable courage and resilience helped to look after the family with her meagre income from labouring in the fields. My “doubtful” uncle has a master’s degree in economics from Gauhati University and teaches in a government school. During elections, he would perform the duty of a presiding officer, even though he was barred from exercising his voting rights for almost two decades.

“D” is not the only category that haunts my family members and me. A few years ago, personnel from the Assam Police’s border unit—which has over four thousand members, who have the power to ask anyone to prove their identity as Indians, and to refer any citizens to a tribunal—raided a rented house in Guwahati’s Dhirenpara neighbourhood, where residents of my village, who had travelled there to work in the informal sector, were staying. The police asked for their citizenship documents, noted down their names and addresses, and took impressions of their fingerprints on blank papers. After almost a year, they started receiving notices from the Foreigners Tribunal, asking them to prove their citizenship. Among those who received these summons were two of my uncles, and one cousin, who sells jhaalmuri—a type of rice puff—on the streets in Guwahati. My relatives were able to successfully defend their citizenship, but I cannot forget the looks of fear on their faces when they first received the notices.

Compared to many others, my family members were fortunate. Even aside from the D-voters, nearly 2.5 lakh people in the state—most of them poor like my uncles and cousin—have been referred to the Foreigners Tribunals under suspicion of being illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. There are cases where government officials, including those from the army, the air force, the border security forces and the police, as well as schoolteachers, have been suspected and referred to the tribunal. There are cases where one person has been referred to the tribunal several times, even after the same tribunal declared them an Indian citizen. The border police is never held accountable for such errors, or for inflicting this burden on citizens—it does this work with absolute impunity, guaranteed under the draconian Foreigners Act of 1946.

The tribunals themselves have become houses of horror for Miya Muslims and Bengali Hindus. The institution is supposed to deliver justice, but has in reality worked like a slaughterhouse, snatching the citizenship and rights of rightful residents of Assam. Like the border police, the tribunals are a one-of-a-kind system, plying only in Assam. The quasi-judicial body hears the cases of people whose citizenship is doubted by the state. The cases are decided not by judicial officers, but by mostly lawyers appointed as members of the tribunal on a contractual basis. There are a hundred such tribunals operating across the state. Their members are appointed by the government, remunerated by the government, appraised by the government, and if found unsatisfactory, shown the door by the government. In 2017, 19 members of the tribunals were removed from office. It has been reported that these members were removed in part because they did not declare enough people “foreigners,” as the border police that referred these cases had claimed they were.

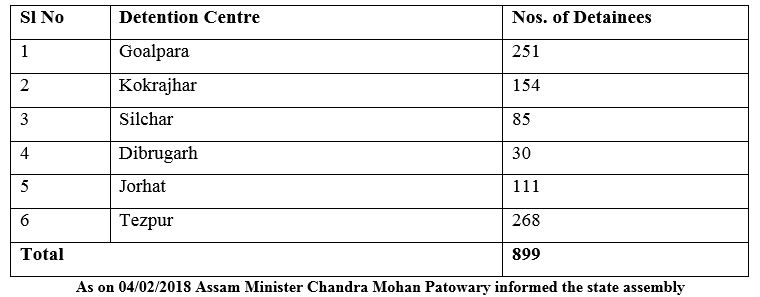

According to government records, over ninety thousand people have been declared foreigners, of which more than twenty-six thousand cases were decided by ex-parte decree in the absence of the respondents. Nearly a thousand of them are being held in six makeshift detention centres, housed inside jails across the state.

I visited several of these jails. I went to the detention centres as part of a research contingent—in January this year, the activist and writer Harsh Mander, then the special monitor of the National Human Rights Commission, invited me to join an NHRC Mission to examine the due process through which a person is sent to a detention centre, study the centres, and assess the human-rights situation of the detainees.

Over these visits, the little hope I had remaining turned into despair. The detention centres are nothing but sections within district jails that have been cordoned off to house those who have been declared foreigners. The detainees are not allowed any formal communication with their relatives. The detainees do not have access to legal recourse such as appeals—the tribunals do not hear appeals, so the detainees can only file cost-intensive writs in the high court or the Supreme Court. Inside the detention camps, they live as convicted criminals.

At a camp in Kokrajhar, I met an elderly woman detainee, who couldn’t stand straight. With her half-bent body, she crawled towards me, and tried to touch my feet. I stepped back. She rolled on the floor of the camp and began howling, with what seemed like all the might of her skinny body. She begged me for death—a mercy death.

I met a woman whose four-year-old son lives in the camp with her. She told me that when she was brought to the detention centre, he was 14 days old. Since then, the boy hasn’t seen the world outside the four walls of jail.

In the Goalpara detention centre, there were more than fifty actual Bangladeshis. Their circumstances showed how little concern the state has for those it deems foreigners. Some of the people we met had been there for nearly a decade, with little or no contact with the outside world. One of the detainees showed me a torn piece of paper with a Bangladeshi phone number. He had memorised the number five years earlier when he was first brought to the centre, and had now scrawled it on the paper, in the hope that he would one day get to call his family and inform them of his whereabouts. While my community is abused as illegal Bangladeshi on a daily basis, while lakhs of us are stripped of our citizenship rights, thousands arbitrarily declared foreigners and hundreds detained, actual Bangladeshis are dying to go back to their country. The government is taking no steps to make this happen.

*

After I returned from the detention centre, the innocent face of the boy continued to haunt me for a long time. Even now, I imagine my son in his place. The very thought sends a shiver down my spine.

I tried thinking of my visit as a privilege. After all, I had a firsthand experience of the horrors that people from my state were being subjected to. I became hopeful. I worked to document every important detail, so that when the report went to National Human Rights Commission and subsequently to my government, it could result in some positive change. My confidence was bolstered by various details that I was privy to—for instance, the mother of the four-year-old child was neither a Miya nor a Bengali Hindu, she belongs to the so-called indigenous Muslim community, a khati—pure—Axomiya. I was sure that my chief minister, Sarbananda Sonowal, who has built his political career on the campaign platform of protecting the rights of indigenous Assamese, would not tolerate this gross violation of their human rights.

But I was wrong again. Mander submitted the report to the NHRC, detailing the inhuman conditions of detainees and the procedural drawbacks of the process, as well as suggesting remedies. The NHRC—the highest quasi-judicial body in the country, which is mandated to protect the human rights of every individual, especially disadvantaged groups such as women, children and minorities—did not respond even after repeated follow-ups. This forced Mander to resign from the position of special monitor. He wrote a compassionate essay calling the detention centres “the dark side of humanity and legality.”

In June, four special rapporteurs of United Nations Human Right Council wrote a letter to the ministry of external affairs, expressing its alarm and concern at complaints it had received about the exclusionary measures being taken by the NRC authority and the Election Commission. The measures, it feared, would exacerbate the discrimination faced by Miya Muslims and Bengali Hindus, “who may wrongfully be declared as ‘foreigners’ and consequently rendered stateless” or deprived “of the right to political participation and representation.”

The letter cast the national spotlight on the NRC process. National and international media, which had so far paid little attention to the issues and concerns of Miya Muslims such as myself, began giving us coverage. No doubt there were issues—a community, many members of which have lived in Assam for generations and have done everything within their power to assimilate into Assamese society and culture, was referred to simply as “Bengali,” either Muslim or Hindu. Nevertheless, these stories highlighted the plight of the Assamese speaking Miya Muslims, especially the role of foreigners tribunal and border police, or the pathetic conditions of people living in the chars of Assam.

I expected that this would help bring some justice to the people fighting the biased tribunal and languishing in detention centres across the state. But the Assamese nationalists had a different plan. A counter-campaign soon ensued in Assamese media, accusing an imaginary vested interest group of acting against the interests of the state, and attacking human-rights workers such as Mander for attempting to throw a spanner into the works of the NRC.

An error-free NRC is not the demand of only the so-called Assamese nationalists, but also for a Miya like me, whose Assamese identity has always been under question. In July 2010, along with three others, my wife’s nephew was killed in police firing. They were protesting against the pilot project of the NRC being conducted. One of the columns in the form led to much anger as it asked for the country of origin. They were demanding an error-free NRC. My community viewed the NRC—a document that would officially grant us our identities—as a weapon to fight the humiliation and persecution we faced.

This belief was systematically destroyed as dozens of exclusionary filters were put into the updating process, including the clause of the so-called “Original Inhabitants” to exclude Miya Muslims and Bengali Hindus. The issue of D-voters could have been solved along with the NRC updating process, but excluding the descendants of people deemed foreigners by the tribunals has created more problems.

When someone raises these questions against these exclusionary and discriminatory processes, they become anti-Assamese even in the eyes of the so-called liberal Assamese intellectuals. My liberal Assamese friends accuse me of not being sensitive to the “threat” they are facing from the supposed large-scale migration from Bangladesh. I almost want to feel this threat, but when I look back at my life, I realise that this threat is me—a Miya.

I think of my mission to be called Axomiya. If I lay claim to Srimanta Sankardev, the architect of modern Assamese society, if I prefer organising Bihu over an Eid mehfil—we stopped celebrating the Bengali New Year over a century ago—if I feel proud when my son sings the songs of the revolutionary Assamese cultural icon Bishnu Rabha, then what threat do I carry? Why do the Assamese chauvinists question my identity despite me having a history of five generations living in this land?

I realise that my Axomiya qualities do not matter. What matters is that I am not them. They are not concerned about deporting illegal immigrants. The “threat” is not about a threat to the Assamese language or the culture—Miya Muslims like me are a threat to their privilege and supremacy.

I do not know how to explain to them how I feel when I see my mainstream Assamese friends and their children being included in the NRC without having to produce so much as a document, while our credentials are examined thoroughly. If the NRC process is a test and everybody consented to participate, why is there not a level playing field?

Even our supposed allies appear not to understand. During the Assam Agitation in the 1980s, when the demand to update the NRC became a point of fierce contention, Hiren Gohain was one of the few intellectuals who described the agitation as hollow. An outspoken public intellectual, Gohain is also a fierce critic of the BJP’s majoritarian rule. But even he couches his descriptions of the suffering of Assam’s Muslims with the terms “seems” and “maybe.”

Although he said in an interview with Al Jazeera that everyone who came to Assam before 1971 should be termed natives of this land, Gohain clarified many things for the people of Assam, especially Miya Muslims, in a recent Assamese-language article. He gave us a suggestion, saying that Miya Muslims “should not forget that seeking safety from platoons of police and CRPFs is delusional. Their safety and the preservation of their basic day to day life is chiefly dependent on the trust and goodwill of the indigenous people.”

If I understand him correctly, I must console myself that my self-respect, my pride of being Assamese, or even my mere existence in this part of the world, is not only dependent on the trust and goodwill of the indigenous Assamese people but also on their kindness and grace. If the indigenous people do not trust us, Gohain appears to be saying that the world’s largest democracy cannot provide us security or protection. Gohain is not just another intellectual— for our community, he was the epitome of courage and struggle. When he suggests that we not seek protection and justice from the state and surrender before the supremacy of indigenous people, I understand why thousands of my community members massacred in Nellie, Nagabanda, Chaolkhuwa, Bahbari, and Khagrabari did not get justice.

Gohain’s words, though hurtful, have a kernel of truth—I no longer trust the state to accept that I am Axomiya, to protect my rights. But I will survive. Swallowing abuse and humiliation has made me resilient. I have learnt how to live like a second-grade Axomiya. I only wonder how to prepare my three-year old son.

Originally published at https://caravanmagazine.in/politics/growing-up-miya-in-assam-how-the-nrc-weaponised-my-identity-against-me

Assam NRC Draft: How Women in Char Areas Were Left High and Dry

Quote Posted on Updated on

The news of four million people being excluded from the final draft of Assam NRC and pushing them to the verge of being stateless has caught the attention of various stakeholders across the country and beyond. The media has also brought out cases of large number of well-established individuals, including a former Chief Minister of Assam, family members of former President of India, family members of former deputy speaker of Assam Assembly, number of armed forces personnel who couldn’t make it to the final NRC draft. But the stories of fear and anxiety of the marginalised and vulnerable sections have still remained unreported.

Among Muslim dominated areas in the state, Kalgachiya in Barpeta district is one of the most affluent with a high literacy rate. According to community leaders and few government officials, only a nominal percentage of applicants have been excluded from the final draft. People who are capable of raising their voice and have access to proper documentation were able to apply and hence made it to the NRC draft.

A visibly anxious boatman said that while his name is there on the list, his wife has not been included in the draft NRC. Most passengers in the boat also described stories of how their family members, mostly women and children, are not in the list.

On the bank of the river, in a crowded small tea stall everyone was speculating about the reason of rejection. Their major apprehension is that the panchayat certificate provided by married women to prove linkage with the legacy holder has been rejected. Gani Dewani, an influential community leader, said, “Only 15-20 families have all members in the list. NRC has divided families with some members being included and others excluded.”

The NRC authority, concerned of ‘breaching of privacy’ of the excluded, hasn’t made the reason of rejection public. Those rejected will have to file another application to get to know the reason for being excluded from NRC.

The discussion in the char village centred around the panchayat certificate and delayed birth certificate. They said initially these certificates were accepted by the NRC authority but later they declined to accept birth certificates and started scrutinising panchayat certificates “strictly”.

Fifty years old Moriyam Begum lives in a tin-roofed house surrounded by the jute and paddy fields in the char. Illiterate Moriyam was trying to find a particular document with the help of her 12-year-old daughter from a pile of papers scattered on the floor. “Keeping documents in order is a challenge,” she murmured.

Almost every year char dwellers experience flood and erosion and often have to move from one place to another. In the last two decades, Moriyam has shifted her residence thrice often taking shelter in the temporary relief camp during the flood. Keeping valuable documents safely becomes a major challenge for these people who are often labelled as illegal immigrants.

Though her husband and eldest son’s name appeared in the draft, she along with two of her daughters and one son were left out from the final draft NRC. Since Moriyam doesn’t have any admissible education documents (only board certificate is accepted), she provided a panchayat certificate.

More than 4.7 million married women submitted panchayat certificate as linkage document out of which 1.7 million women were brought under “original inhabitants” status, a privileged category and were exempted from the stringent verification process. However, Muslims and Bengali Hindus, didn’t fall under the category thus despite being from one of the most marginalised social groups, Muslim women from the char areas had to go through a stringent verification process. Moriyam is one of the 2.9 million “unfortunate” women who submitted panchayat certificate.

It is speculated that most of these Muslim women are from char areas of Assam, which accommodates nearly 10 per cent of Assam’s population. There are more than 2,200 river island villages spread over 14 districts in Assam, which are geographically plagued with floods and erosion.

As per the last survey by Assam the government in 2002-03, as many as 68% of char people live under the below poverty line (BPL) and over 80 per cent of them are illiterate. Assam Human Development Report (2014) says that the Mean Year of Schooling (MYS) in char areas is 4.76 years which is the lowest among all marginalised communities in Assam. The abysmally low female literacy rate was one of the reasons of higher number of women submitting panchayat certificate from these areas.

Another reason that is equally responsible for making the char women most vulnerable in the NRC updating process is the feudal legacy and continuance of core patriarchal practices like child marriage. A study conducted by Manoj Goswami says that in char areas the mean age of marriage remains low 17.1 years.

National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 4 data reveals that in char dominated districts nearly half of the women get married before the age of 18. When women are married off before attaining the age of 18, they miss the opportunity to get enlisted in the voters list in their parental house. In absence of other documents (read educational document), it effectively delinks them from their parents and forces them to use panchayat certificate to prove linkage with parents. If they were married after getting enlisted in the voters list at parental address i.e. after attaining the legal age of marriage, they could have used the voter’s id for linkage

Today, it seems the “masculine state” is hell bent to snatch the citizenship right from women like Moriyam. She hasn’t been able have proper sleep and food ever since the final NRC draft was published. Now her only concern is ‘would they send me to ‘Kalapani’?’ She used the infamous cellular jail in Andaman and Nicobar Island to describe possible detention centres.

Originally published at https://www.news18.com/news/opinion/assam-nrc-draft-how-women-in-char-areas-were-left-high-and-dry-1835325.html

How Sword of NRC is Destroying Families in Assam

Quote Posted on Updated on

On a soaring summer morning, Ilim Uddin Dewan (50) drove his SUV to the Chenga Circle Office in Barpeta district of Western Assam. He met the circle officer, the executive magistrate of the revenue circle and the designated Circle Registrar of Citizen Registration (CRCR), for the National Register of Citizens (NRC) within the jurisdiction of revenue circle area.

Ilim Uddin, a middle age successful businessman and politician, who fought for assembly seat in 2011, alleged that his wife Mamataz Dewan was harassed in the name of being illegal immigrant from Bangladesh. A case under Foreigners Act was referred by the border police to foreigner’s tribunal in 1997 and the tribunal upheld her Indian citizenship in 2016 after a decade-long legal battle.

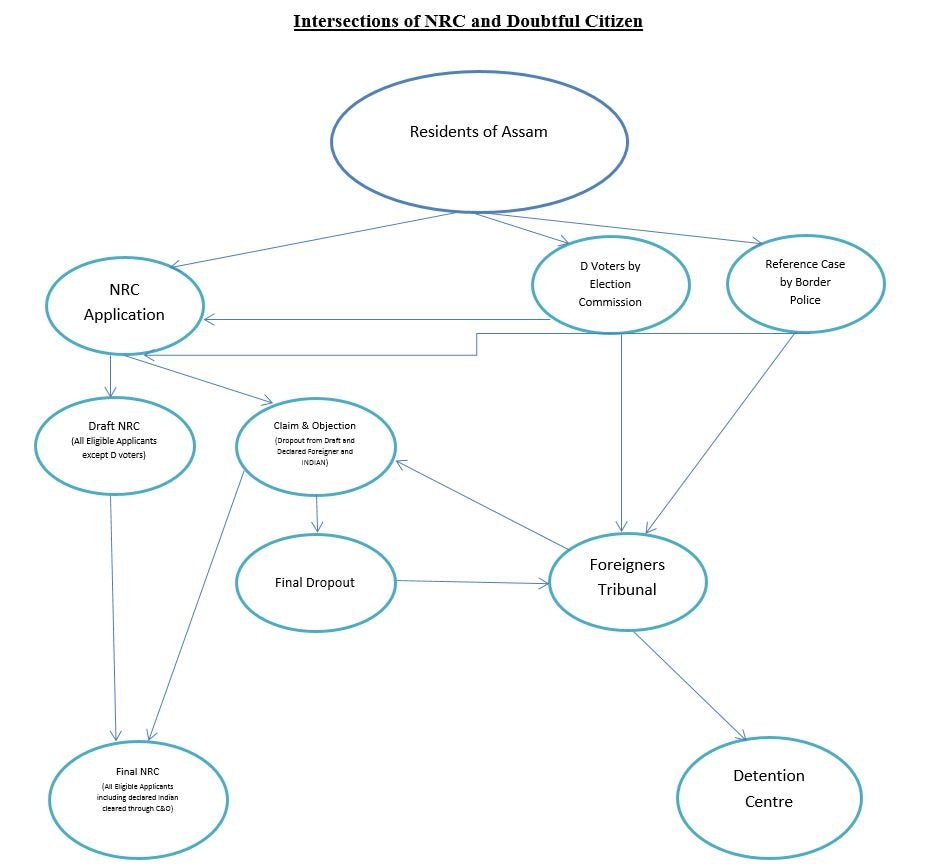

The NRC coordinator Prateek Hajela has said time and again through the media that once the alleged foreigner or D voter gets clearance from Foreigners Tribunal and found to be Indian citizen will be included in the NRC. The NRC website also says “D voters can apply for inclusion of their names in the updated NRC. However, a D Voter’s name will only be included in NRC only after getting clearance from the Foreigners Tribunals.”

However, the Circle Registrar of Citizen Registration (CRCR) Rajiv Kumar Das said “My hands are tied; I can’t do anything. We are doing what the state office has instructed us to do. State office has a sent list and asked us to keep those names on hold, I can’t do anything”. As per media report, the NRC authority has blocked 63,000 D voters or doubtful voters.

The officer inquired with his junior officer and confirmed that the database sent by the state office contains her name. “Even though you won the case, I can’t accept the papers,” said Rajiv Kumar and advised Ilim Uddin to contact additional deputy commissioner, who is his supervisor if a person is not satisfied with the officer’s response.

The persons, who have been declared as Indian national by foreigner’s tribunal since 2015, will have to wait till the complete draft is published. They will have to go through the claims and objection process along with those whose name do not appear in the complete draft. A window of one month will be provided for re-examination citizenship documents who wouldn’t figure in the complete draft or someone who is wrongfully included in the list.

How Significant is Doubtful Voters in NRC?

In March 2018, Assam Minister Chandra Mohan Patowary informed that state assembly that as on December 31, 2017, there were 4,85,640 D voters and suspected citizen (2,44,144 D voters and 24,14,96 reference cases), out of which 2,40,583 (1,31,034 D voter and 1,09,549 reference cases) were disposed of. The foreigners’ tribunal has declared over 92,000 persons as foreigner and remaining were able to prove their Indian citizenship.

However, out the 92,000 declared foreigners nearly 15,000 declared foreigners were found to be pre-1971 immigrants, who are treated as Indian citizen as per Assam Accord. Interestingly, over 26,000 cases out of the declared foreigner cases were declared as foreigner through expatriate decree. That means that those 26,000 declared foreigners didn’t appear before the court and court didn’t examine their citizenship credential. On other words, in many cases, those so called declared foreigners even don’t know that the foreigners’ tribunal has declared them as foreign national!

On May 2, the NRC coordinator Prateek Hajela sent memo to all district magistrates to block the name of declared foreigners and their family member’s names entering into the complete draft NRC. The NRC coordinator says that the letter has been issued based on an order given by Gauhati High Court last year. Considering the timing and far reaching and retrospective impact of the letter, the religious and linguistic minority communities perceive it as a ploy to exclude large number of genuine Indian citizen from complete draft and make them vulnerable for torturous battle in the foreigners’ tribunal and augmenting the risk of landing in the detention centre.

However, NRC coordinator has clarified that out of 92000 plus declared foreigner they could have identify only 4259 applications submitted by those declared foreigners. He speculated that the number of family members of the 4259 declared foreigners would be around 50000.

Meanwhile, the decision of excluding the family members of declared foreigners, who have documentary evidence to prove their Indian nationality and whom the NRC updating authority itself had provided the legacy document, not only created public outcry in Assam but also got attention from national and international media as well human rights bodies and human rights defenders.

Opened the Pandora’s Box?

On June 11, four Special Rapporteurs of United Nations Human Rights Council has sent a strong communication to the MEA Sushma Swaraj. The eight pages letter alleged that the order “may lead to the wrongful exclusion of close to two million names from the NRC, without a prior investigation and trial.” The letter also questions the independence and impartial functioning of foreigners’ tribunal and terms it as “so-called foreigners’ tribunal”.

It labelled serious allegation “members of Foreigners’ Tribunals in Assam experience increasing pressure from State authorities to declare more persons as foreigners. On 21st June 2017, 19 members of the Foreigners’ Tribunals in Assam were dismissed on ground of their under-performance over the last two years. More than 15 additional Tribunal members were issued with a strict warning to increase their efficiency. Considering that tribunal members serve on a contractual basis for two years, which may be extended on a needs and performance”

One of the terminated members of foreigners’ tribunal, on the condition of anonymity said that one of their performance indicators was – how many cased they decided in favour of the state’ or in other word how many cases they declared as foreigners!

In the wake of the controversy regarding the May 2 letter of the NRC coordinator, another important and shocking development is observed. Earlier this year, noted human rights worker and former IAS officer Harsh Mander led the National Human Rights Commission’s Mission to detention centres in Assam as Special Monitor to NHRC. His mission studied the conditions of detainees inside two detention centres in Goalpara and Kokrajhar district of Assam and studied the process of the identifying doubtful voters and functioning of border police who refers cases to foreigners’ tribunal. Harsh Mander submitted the report but NHRC didn’t take any step on his findings and suggestions. He resigned from NHRC as Special Monitor and made his report public.

The report alleges “these detention centres lie on the dark side of both legality and humanitarian principles”. There are nearly 900 hindred declared foreigners who are detained in six detention centres across the state. Some of them are detained for nearly a decade. Their families have been separated; they don’t have any right to payroll, means of communication with the family members. There is no manual or proper guideline for the administration of these detention centres. In one hand the detainees are treated as convicted criminals on the other hand they are not allowed the basic rights like payroll and wage against which are available to convicted criminals.

Harsh Mander further wrote, “Overall, I am convinced that for a process that can result in the disenfranchisement, indefinite detention or expulsion of a person, the state government needs to ensure due process and, with it, compassion and an understanding of the predicament of persons with a poor education and lack of economic resources and social or political capital.”

However, the Assam government and the NRC authority have not reacted either to UNHRC Special Rapporteurs letter or Harsh Mander’s report.

Changing Narrative

The citizenship tangle in Assam has a long history and many complexities. Apart from the administrative complexities involving multiple agencies, nearly a dozen of Acts, Rules and Accords, numerous state and non-state stakeholders; the complexities of narratives are also emerging.

The narrative of large scale, uninterrupted influx of migrants from Bangladesh causing threat to demography, language and cultural heritage of Assam has been slowly shifting towards the narrative of persecution and mistreatment of genuine Indian citizen who are religious and linguistic minorities in the state of Assam. There is little doubt that the ‘doubtful voter’ and its ecosystem has been the breeding ground for such counter narrative and the May 2 letter issued by NRC authority has given the long awaited exposure to the issue.

This will be interesting to observe how the things get unfolded once the complete draft NRC is published.

Originally published at https://www.news18.com/news/india/despite-valid-documents-my-wife-is-a-doubtful-citizen-how-sword-of-nrc-is-destroying-families-in-assam-1827111.html

Politicans playing dirty over displaced Bodos in BTAD: Promising Land Patta inside Forest

Quote Posted on Updated on

This is election time in Assam and political parties are not leaving any stone unturned to get as much vote as possible. If someone is promising to create 2.5 million jobs in next five years, other one is promising to protect civil and human rights of the persecuted minorities. In reality, all these hollow promises will be going to the cold storage of politicians’ conscience without a second thought. However, one such hollow promise and great deal of hypocrisy paining me since 29th of March, 2016. Deputy Chief of Bodoland Territorial Council Khampha Borgayari conducted an election meeting at a newly encroached forest village called Laimuti on 19th of March, 2016. Mr. Borgoyari promised to provide land patta along with other services to the forest dwellers who settled in the forest most recently. But to know more about his hypocrisy and political gimmick, let me take you through the village.

Three of my colleagues along with our local resource person Dan Narzary, we crossed the bamboo bridge over river Chapma a beautiful place around 10 kilometers from Runikhata under Chirang district of BTAD in Assam. River Champa is a narrow but powerful river as its water follows fast and during monsoon it becomes ferocious. A middle age man was hurling his fishing net near the bamboo bridge. The big trees in the upstream of the river made the scenario picturesque.

Soon after crossing the bridge, we found a small hut on the bank of river Champa. I talked to Dhaneswar Basumatary – the owner of the hut. His family members were busy in planting tapioca tree. His son was cutting the tapioca tree into equal pieces to plants. The plant was new to me; our local resource person Dan Narzary who did his masters in Ecology, Environment and Sustainable Development from Tata Institute of Social Sciences introduced the tapioca plant as a “poverty resilient food”. The hut itself was enough to correspond to the level of poverty faced by the family. But the story of tapioca escalated the brutality of poverty and hunger. Dhaneswar Basumatary’s family was forced to move into the forest in 2005 to live such a miserable life when his 8 bighas (over a hector) of agricultural land was eroded by river Champa. Dhaneswar Basumatary is not the only victims of river erosion, many of the forest dwellers of the area were uprooted by river erosion.![DSC_0073[1]](https://abdulkazad.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/dsc_00731.jpg?w=705)

It is worthy to give a glimpse of the larger picture of erosion affected people of Assam. Study revealed that in 50 years (1950 to 2000) river Brahmaputra alone had eroded 7 percent of Assam’s total land and tens of thousands people have been displaced. Till 2015 Assam Government didn’t have any rehabilitation programme for the erosion induced IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) of the state. In March last year, Assam Government came up with a scheme called “Chief Minister Special Scheme for the Erosion Affected People”. The scheme talks about providing land as compensation for both homestead and agricultural purpose, if government land is not available cash compensation is to be offered. But the scheme remained defunct for almost a year. No effort was made by the government to disseminate the information regarding the scheme among the displaced people. We tried our best to make the affected people aware about the scheme and encouraged them to apply for compensation. But nothing happened till January 2016 and finally I filed a RTI petition seeking some crucial information like how many applications received and processed etc. Assam State Disaster Management Authority which is the nodal agency for implementation of the scheme; scandalously replied my RTI petition saying that the agency had not received any application! Later on one of my journalist friends investigated the matter and revealed that despite no promotion and advertisement, ASDMA had received a large number of applications and as the agency couldn’t deal with such huge number application. Before replying my RTI government changed the scheme through another circular. The modified scheme is equal to nothing! The government has modified it in such a way that almost no erosion induced IDP can avail any benefit under the scheme. This kind of government indifference and apathy have been pushing the erosion induced IDPs to settle generally in forest areas and to migrate into urban areas for livelihood.

We continued walking through the path recently cleared by chopping down the trees in Laimuti. Though the roots of big trees were burnt down to decompose early but are still visible thorough out the fields. Dan Narzary lamented that, being a professionally trained environmentalist he felt like crying after seeing the destruction of the forest just 10 kms away from his house. He feels that tribal people are losing their belongingness towards forest and overlooking the importance of forest conservation. He pointed out a number of factors which attributed towards this change in attitude. At one hand poor people are being uprooted by river erosion, violent conflict and they are not compensated by the state. On the other hand the government forest department is destroying the forest by partnering with smugglers. How the poor people can think about conservation of forest? Dan questions.

By the time we reached the village market in Laimuti it was late afternoon. The village headman Sukur Basumatary took us to an open school. Few fixed desk benches and a pair of wooden chair-table and a tinned roof hold up by not many concrete pillars were the only infrastructure in the school. However, name of the school Rwdwmkang which means ‘uprising’ in Bodo language actually points towards the aspiration of the villagers. More than 50 students are getting educated without any government support. The villagers collect money and other resources among themselves to pay the monthly salary of Rs. 1000/- to the teacher. Around 8000 people are living in 25 forest villages in Laimuti area without a single government school, no Anganwadi centre, no health facility, no source of drinking water or any other government services. In other words, they are still living right inside the forest, where there is no presence of government.

Three out of the 25 villages faced retaliatory attack from Adivasis on 25th of December, 2014 i.e. two days after the massacre of over 70 innocent Adivasi people by suspected NDFB (S) militant in Sonitpur district of Assam. At least 23 houses in those three villages were burnt down to ashes by the miscreants. The Bodo inhabitants were forced to set up shelter camp in Laimuti market. Hundreds of terrified Bodo men, women and children had continued to live in the camp for over two months without any support from government. Chakra Basumatary one of the victim said “forget about relief, rehabilitation or compensation, no government departments including police department didn’t visited the affected villages”. When one of the civil society organizations took the victims to government office in Kokrajhar, the victims were abused by the officials and their request for compensation was out-rightly rejected.![DSC_0113[1]](https://abdulkazad.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/dsc_01131.jpg?w=705)

Mr. Khampha Borgayari who served as Deputy Chief of BTC in the previous term also never did anything to minimize their suffering, even during the toughest time of arson and forced displacement. The villagers at Laimuti said that Mr. Borgayari is now campaigning for his colleague Chandan Brahma and he has promised to provide land pattas along with other services like education, health, water etc.

If this is the fate of displaced Bodos – to protect whose right the territorial privilege was granted, then anyone can easily imagine the condition of displaced non-Bodos living in the model BTC!